Since 1890 we’ve housed hundreds of thousands of people. From the red-brick tenement blocks in London to modern eco homes in rural areas, we have always strived to provide our residents with safe and comfortable homes that meet their needs.

During the first twenty years of The Guinness Trust, we replicated the architecture and management of other charitable and model housing organisations. However it’s thought that life in a Guinness building was a little easier. The rents were cheaper and aimed at supporting the “labouring poor”, with “early rent registers listing labourers, stablemen, porters, shop-workers, charladies, seamstresses, kitchen maids and it was rare to find a weekly wage in excess of £1.” (Annual Report and Accounts, 1979/80)

Guinness provided a number of extra services to tenants – hot water in the yard, urns with boiling water in the mornings and evenings, club rooms stocked with newspapers, books and games. The clubrooms were closed in the 1920s, as gas supplies to the tenants’ flats meant people used these rooms less. Many were later turned into lunch clubs and community halls.

“‘You going to the clubroom tonight?’ Derek asked. He was referring to the large meeting hall which ran above the superintendent’s flat, workshops and boiler rooms. It was the equivalent of a village hall and held dance and gymnastics classes to bridge, gardening and film and variety shows. The hall had its own well-appointed kitchen and toilets. The dance floor held two hundred dancers with ease on its sprung maple floor, with a raised stage at one end accommodating the film screen, bands and other acts. It was in the centre of our flats and was the hub of our social life.”

Bill Brown, Billy Brown, I’ll tell your Mother, 2011, talking about the clubroom at Loughborough Park

The rents had to support management and maintenance expenses, rates and charges to pay for these services and others, including hot baths in the bath houses and chimney sweeping. In addition, the Trust purchased coal at summer wholesale prices and sold it to tenants at a low cost. Lady Iveagh even set up a nursery at the Brandon Street estate, where children under five were looked after for 3 pence a day. (Malpass, 1998)

Regimented tenement blocks, iron railings and ex-military superintendents: the model estates of the early 1900s would seem austere today. But the charitable trusts that set them up were trying to provide safe, hygienic and orderly homes as alternatives to slum housing.

And it was noted that the Guinness Trustees had given more thought than others to making the buildings comfortable and appealing to look at.

“In the new Guinness buildings the disadvantages of the block system will be minimised, and the red brick exterior has far more ornament about it than ordinary buildings of the ‘Peabody’ types. Each family will be supplied with every convenience, and each suite of rooms will be abundantly supplied with the prime necessities of life: air, water, heat and light.”

South London Press, 14 March 1891

“The buildings are really attractive-looking, in bright-red brick, with balconettes for flower-pots on the window-sills and bas-relief decorations over the doors, such as ‘Home, sweet home’”

The Quiver, 1900

And many tenants were pleased to get a home in a Guinness Building.

“Criticism of the barrack-block appearance of the new building were rightly ignored. The four blocks with their cemented spaces or yards in between were an infinitely better place to grow up in than most of the streets around World’s End… the Trust’s draconian rules on window cleaning and the tenant’s responsibilities to wash down the white-tiled landings on a rota were welcomed by many who had fled from the multiple occupation of crumbling Victorian houses in the area. The new flats on King’s Road, or tenements as they were called, provided low-rent basic living: gas lighting (although to be fair all the streets at the time were gas-lit) rather than electricity, and outside lavatories on a small cast-iron-fenced balcony. Washing facilities were a bath with a hinged pine top in the kitchen scullery… But the flats were light, comfortable, and warmed by a kitchen range in the front room.”

“Over Lantyne Street, Lupus, Seaton, Slayburn, Vicat, Bifron, Meek or Stadium, Guinness Trust Buildings represented an enormous improvement. In the large open space between each block young children could play safely; marbles up against the wall, a rough and tumble game of Warney Echo when in season, skipping for the girls and football with a tennis ball for the boys. Guinness Trust Buildings promised a good life.”

Donald James Wheal, World’s End, 2005

Many of the first London buildings were built in uninhabited or dilapidated areas of London, where it’s assumed they improved the quality of housing and lifted population numbers. It’s a foundation that we’ve stuck to today, building and developing communities across the whole of the country.

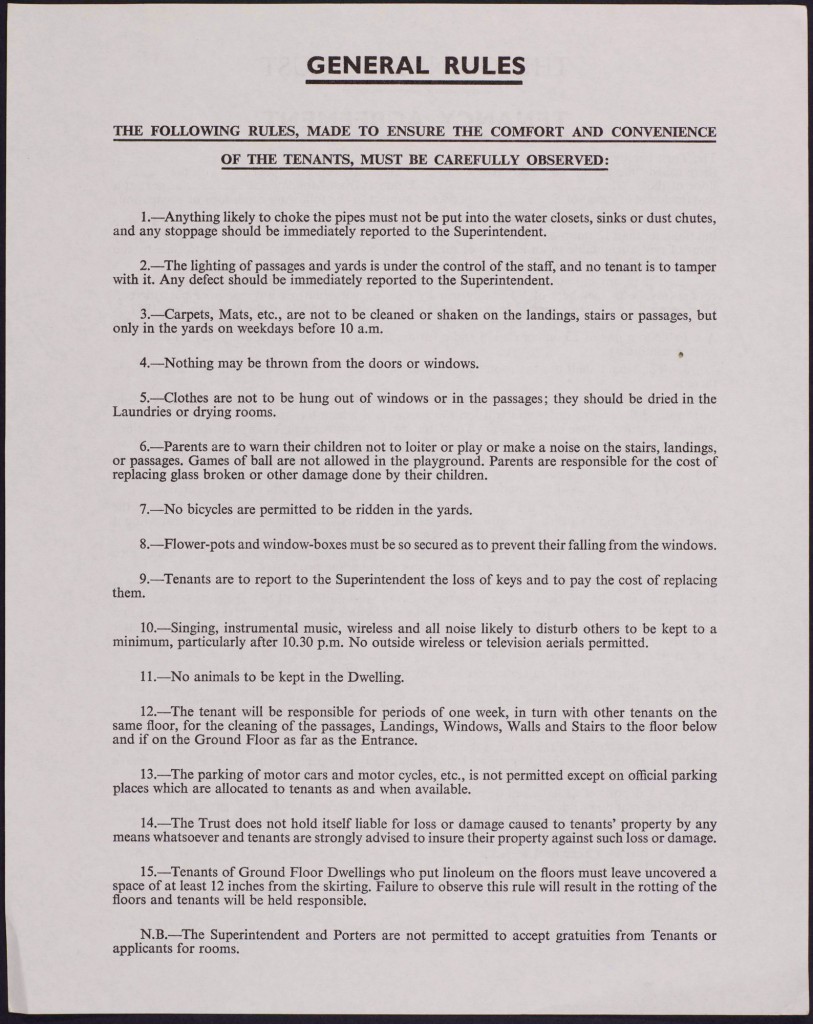

To meet the Trustee’s high standards for moral and hygienic order, the rules of a Guinness Trust building were strict, though they loosened as the years went on.

The tenement blocks were kept meticulously clean, with rules to keep living and communal areas scrubbed and free from clutter and banning wallpaper. Prospective tenants even had to prove that they had been vaccinated before being given a home. (Malpass, 1998)

“New tenants had to answer a very critical string of fifteen questions, subscribe to fifteen conditions of tenancy, and declare allegiance to fifteen rules which govern the institution.”

Yorkshire Post, 12 December 1891

You can read some of general rules from the 1930s below.

“Landings and stairs struck me as particularly clean: tenants must take their turn in keep [sic] them so… No drunken or disorderly person, no person below a certain standard of cleanliness, may hope to remain a permanent tenant. An outburst of hilarity, a little conviviality may be overlooked once or twice: patience is shown with ladies whose standard of cleanliness falls below the mark. But drunkenness or dirt will not be tolerated.”

The Quiver, 1900

Today these strict rules have been replaced with our customer handbook, which helps our staff to work with tenants and provide a safe and comfortable place for everyone.

Former tenant, Karen Jones, remembers growing up on the Vauxhall Walk estate

Four generations of my family have lived at Guinness Trust. I remember Thursday night was ladies’ and childrens’ night to use the communal baths. We would choose a partner and share a bath taking our towels and our best toiletries. There was a lovely old lady who would run your bath for you and clean it after use.

The flats were kept spotless in all communal areas. At eight o’clock a porter would call “allie allie in” and all the kids had to go home. If you got found still outside he would personally escort you to your front door and tell your parents.

A look at our tenancy records shows the movement of tenants in and around our estates as families grew and migration outside of London began. Some of our customers have lived with us for many years, while others have seen generations raised on the same estates.

Snowsfields

Snowsfield was like, oh, utopia. You had your own bath in the kitchen, and you used to have a top, like a, well it would be like a pine top, and you used to work on that in the daytime and take the top off and have a bath in the evening. I mean to have your own bath was amazing, you know. My mother thought she’d died and gone to heaven.

King’s Road

It was a very friendly estate. But it was commanded then by a Superintendent, so he used to make sure that everybody was on their toes and the ladies used to be told off if they were gossiping in the yard. They were told that idle gossip causes problems so they were told to go back to their flats. It was quite strict and they used to have ‘all the up’ where everybody had to be up by a certain time. In the evening they had a curfew for the kids; 7 o’clock in the winter and 8 o’clock in the summer.

Tony recalls his time growing up at Stamford Hill, and his mother’s 89 years with Guinness.

My story starts with my mother, Ivy Dorothy Moore, who was born in August 1918 in Tower Hamlets, Bethnal Green. She lived at the Colombia Road estate with her parents, one brother and four sisters. As a large family, her parents and brother lived in one flat and the four girls lived on the next floor.

Moving to Stamford Hill

Soon after Stamford Hill opened the family moved to Flat 31 and then down to 28, to a two-bedroom flat. When mum married Walter, they took flat 16.

My brother was born in January 1944 and I came along in March 1946, so we moved to the ground floor, into Flat 41. I was there for 19 years and my brother for 25.

When Dad retired they applied to move to Panshanger at Rupert House, and then moved into the Warden’s Block at Iveagh House when mum retired.

Celebrating 82 years at Guinness

On her eighty second year as a tenant the then Group Director Jeff Baker made a presentation of flowers and a commemorative book, and arranged for a car to take Mum and Dad back to Columbia Road for a tour. The block had undergone a complete renovation and they even made it to the roof to view the old neighbourhood.

Dad died in 2007 and mum eventually went into care, so after 89 years of unbroken tenancy, she left Guinness.

My memories of living with Guinness

I can remember three caretakers. A lovely chap named Mr Whiteman, an ex-army chap named Wilcox, and then came Mr Smith. There was once a caretaker called Scutt early in the 30s or early 40s – I was friends with the Scutt family who had several family members in the Stamford Hill estate.

After mum’s parents died, the flat at Number 28 was taken over by mum’s two sisters, Mary and Leah. Mary moved to a Guinness estate in Basildon and Leah moved to Iveagh House in Lambeth. Dad’s brother Leslie Calver and his wife Phyllis also moved to Iveagh House.

So I guess you can say the Guinness Trust was part of our lives for a very long time!

Elaine shares her memories of growing up on the Vauxhall Walk estate with her family.

My family was vast, the Young’s and the Hibberds’ – we lived in blocks B, D, E, F, K, and M at the Vauxhall Walk estate.

Mr Chapman was the caretaker at the time; Len and Frank were the porters. My nan was the person you went to for births, deaths and everything in between.

My two favourite places were the wash house and the basement baths. The baths were huge – I could almost swim in them. The buildings had many characters and there was a bond between neighbours at that time.

Albert tells us why moving to the Fulham Palace Road estate was the best decision he’s ever made.

I moved into Fulham Palace Road in 1969 and I can honestly say it was the best move I ever made. Top floor in J block was the first flat I lived in and my brother had the flat next door. In 1980 I moved into my present flat and I love it. Hammersmith must be the most desirable area to live in with the underground stations and easy access to the airport.

Memories of the estate

I remember when we all had to take turns to wash the stairs, toilets and bathroom – it was a mad rush especially in the winter.

When I first moved here there was a gate at the entrance to the buildings that drivers had to get out and open to gain access. Can you imagine that being there now with the traffic on Fulham Palace Road?

Royal visitors

Princess Diana visited on 17 September 1987. It was a nice day for the estate. She was very pleasant, speaking to lots of us and going into one of the neighbour’s flats, it was very memorable.

David Copping’s family lived on our London estates for 112 years

Generations at Draycott Avenue

My family’s association with the Guinness Trust goes back to 1893 at Draycott Avenue, Chelsea. The 1901 census shows my maternal great-grandparents – Francis and Eleanor – living at 78, C Block with three of their children. My nan, Caroline, was away at boarding school: her education was paid for by the Earl of Bradford. Later she worked as a general maid for the Earl, and his wife, Lady Bradford, was her godmother.

My other maternal great-grandparents, William and Mary were living at 287 and 288, G Block with three of their children, including my grandfather, another William. One of the children appears to be Mary’s from a previous marriage. She was William’s third wife and she would re-marry after his death. He was a copying clerk to the guardians of the Workhouse.

My paternal granddad, George, moved to London from Smarden, Kent looking for work around the turn of the century. He married Ada and, after a few years in Kent looking after his mother, they moved back to London in 1909 to live at 81, C Block with three of their children. George worked as a platelayer on the London Underground.

My great-granddad William died in 1903, and Mary and the children continued to live at 287, H Block. Francis continued to live at 78, C Block with two sons and two daughters until his death.

My grandparents William Baines and Caroline Phipps married on 27 August 1913. There is evidence that this was accelerated as their first child was already on the way! The family lived at 279, G Block and had three sons and two daughters, including my mother, Maisie, who was born in 1926.

The family during the wars

William and his brother Thomas were both conscripted to the army in 1918 and sent to France. Thomas died in action and is buried near Armentieres. William was taken prisoner in the same action, sent to Germany and made to work in a coal mine. William’s second brother – Edward – emmigrated to Australia in 1913 and enlisted in the Australian Army in 1916. He returned to Europe as an ANZAC and was sent to France, returning to Australia in 1917 when he was invalided. You will find my Grandfather W.C. Baines, W. Savage, W. Crowley and T. Smith (the last three are my great-uncles by marriage) all mentioned on the Draycott Avenue memorial to those who fought in World War One.

My father, Walter, was born in 1914 and both he and my mother served in the army during World War Two. My father enlisted in 1935 as a Hussar and was posted to India, and later Iraq. He was posted home in 1943 and was seconded to the military police just before D-Day. My mother was called up to the Auxiliary Territorial Service, and served with the Royal Artillery in the 93rd Mixed Searchlight Regiment. When they left the army in 1945 and 1946 respectively, my mother returned to work at Peter Jones and my father back to his old profession as a clock repairer at Didbins in Sloane Street.

My parents meeting in Chelsea

My dad was living with one of his sisters in 280, G Block, which was on the same landing as my mum’s family. One day he asked mum out for a ride on his motorbike and she accepted: the rest is history. They married in 1947 and I was born in 1948.

On 23 December 1946 my dad applied for a vacant flat in Draycott Avenue. After thirteen months, on 2 February 1948, he applied for a transfer to 27, Kenwood House at Loughborough Park, in South London. It was a nice, new, modern estate, and all his friends and family told him that he had no chance. But the transfer was approved and my parents moved into their new flat. Eight years later, we applied for a mutual exchange from the two rooms of 27, Kenwood House to the three rooms of 101, Elveden House.

Many other members of the family continued to have a connection with Guinness: by the time my mother died in 2005, my family had been living in Guinness homes for 112 years.

Life in the Guinness buildings

If there are any photos of Draycott Avenue before the modernisation I’m sure they would shock a few folk. The flats consisted of one room with two smaller rooms leading off. Two WCs, two laundry rooms and two communal sinks each with a cold tap per landing. Lighting was by gas, heating and cooking by a solid-fuel range. There was no electricity: I recall Grandparents Bill and Caroline were still using a wireless powered by an accumulator in the 1950s. Auntie Bess had a radio rented from British Relay Wireless. BRW cabled up the estate for radio and TV came later when electricity was laid on. There was just one communal bath house and the porters’ wives had duties there. You had your day and time for your bath. If you missed it for any reason – tough! You had to wait until the next week.

The Loughborough Park estate in Brixton is now being replaced with a new, modern estate. It’s a shame to see the old flats go, but in all honesty, I would not want to live on the old estate again. Compared to Draycott Avenue at the time, Brixton was a palace, but the flats were unheated and draughty. Going to bed wearing a thick jersey and woollen socks was not uncommon! The friendships I made continue to this day.

Pamela Finn, a former resident, recollecting her life at Page’s Walk

We moved into 37B, Guinness Buildings, Page’s Walk in 1958. The rent was 13 shillings and 6d a week, payable by 3pm on Friday.

There were four flats on each floor. Two toilets and a laundry washroom were shared by the four families. My husband Ron used a concoction of chemicals to clean the toilets once and almost blew himself up!

The accommodation had two rooms; a living space that also was used for cooking and a bedroom, about 12′ x 6′. There was no electricity so we didn’t have a conventional radio. Radio Rentals ran a piped service into the flats.

Ironing was a bit difficult as I had to use an old-fashioned flat iron, two in fact, one to heat up on the gas stove, while using the other. I still have one of them that I use as a doorstop!

In 1959 our son Cliff was born and the bedroom was given over to the children. We slept on a put-u-up in the living area. In 1962 our daughter Julia was born. It was becoming quite crowded and we were offered a ground floor flat with two bedrooms.

The following year we moved away from London and the Guinness Trust to Bromley, to a house with four bedrooms, a huge living area, kitchen, pantry and a garden. The rent was £5 per week, payable three months in advance, but we were in heaven!

Having said that, we were extremely grateful to have been given the flat at Page’s Walk and thank those Victorian philanthropists for their care.

Peter Voss, a former resident, reminiscing about his family’s home at Page’s Walk

I lived in Guinness Buildings in Page’s Walk, Bermondsey (just off the Old Kent Road). The flats were large Victorian blocks built by the Guinness Trust for poor people. There were Guinness Trust buildings all over London. The flats were not luxurious by today’s standards. There were four large blocks of buildings and each block had about six entrances. These entrances led to concrete staircases and there were four flats on each landing. The size of the flats varied, but most were just two rooms.

When my mum and dad first married in 1951, their rent for a one-bedroom flat at Page’s Walk was 7s 8d (about 38p), which I believed included the rent and water rates. Dad was earning about £7 a week in those days.

A living room/kitchen (this had a range –coal or gas – but no running water) and one bedroom. The toilets and sinks (two of each) were outside the flats on each landing and were shared by four families. The baths were in two separate blocks and it was possible to bath on only two days a week. My grandfather was one of the caretakers (they were called porters) and one of his duties was to stoke the boilers to heat hot water for the baths. The baths were in cubicles and you had to pay (I think it was 2d) and he would run the bath for you. There were no taps; he had a brass tap which fitted on the square spindle to operate the tap so you couldn’t take extra hot water. There was no electricity in the flats; all the lights were gas mantles. I lived there as a small child until about 1960 and they eventually put in electricity in about 1962/3.

The flats were demolished in about 1970 and brand new flats were completed in 1972, which are still there. We moved away to Guinness Buildings in Kennington Park Road (where we had our own bath!) and they are also still there.

When we were kids in the buildings, there were four front doors on each landing (two each facing each other). All the doors had knockers and we used to tie all the knockers together and bang one. When the person opened the door, looked and saw nobody there, they shut the door which then let the string go making the other knockers bang on the doors. It was great fun.

I also remember ‘bagwash’ days at the flats. There were no washing machines or facilities (except sinks) and most people sent their washing to a local laundry, Maxwells. They used to come round in a van and the driver used to shout “BAGWASH” at the top of his voice. This was a signal for dozens of windows to fly open and large white sacks containing dirty linen were then thrown out (even from the top windows!) to the driver. Not a good place to be walking past.

My granddad, George Horton, was the porter at Page’s Walk for most of his working life and he retired aged 72 in the late 1960s. Even at that age he used to carry hundredweight sacks of coal up all of those stairs whenever tenants required it. He also swept all the yards by hand with a massive broom every day.

Clara Smith’s family lived at Vauxhall Walk in the 1970s

I lived in a Vauxhall Guinness Trust property as a small child until 1974 – I would love to see more photos of those flats. I remember baths in the butler’s sink, sharing the toilet on the landing with the neighbours and playing in an abandoned car in the square between the blocks.

Maureen Laing talking about her family who lived at Draycott Avenue before emigrating to Australia

My grandmother, Mary Frances Sherwin was born in Pimlico on 8th July 1902. Her parents were Robert William Sherwin, a War Office messenger and Mary Ann (nee Hawley).

In the 1911 Census she and her parents were living in 129 Guinness Buildings in Draycott Avenue, Chelsea with three siblings: Robert William (jnr) born 5th July 1903, Margaret, born April 1905 and George Lambeth, born April 1907 (all in Chelsea). Her father was still listed as a messenger for the War Office and continued in that work at least until his wife’s death in 1933. In all that time they were living in Draycott Avenue.

I’m not sure if they moved from flat to flat at all because for the most part they were recorded as living in 129 but in 1933, in Mary Ann’s notice of will she was recorded as living in 128. In 1926 Robert Jnr travelled to Australia. He was almost immediately hospitalised with tuberculosis, with government records stating that he was a non-assisted passenger, a university student of 23 years old. Later investigation (so that he could be sent home when recovered from his illness two years later, noted that his parents resided in 129d Guinness Buildings. Perhaps 129 was the floor number, with a,b,c and d the unit designation?

In 1912 (at 10 years of age) my grandmother, Mary Frances, was brought out to Australia by her grandfather, Joseph/John Hawley to keep house for him. Perhaps it was in the hope that her life would be better or perhaps because none of his own adult daughters or his wife were willing to travel.

Her sister Margaret met and married William Norman Inns (born 6 Oct 1904) in 1925. He lived in 247 Guinness Buildings, Draycott Avenue with his father, James, a milk carrier, his mother Lillie/Lily and his brothers George and Walter (1911 Census). Margaret and William had two sons, Charles William (b 1927) and Robert James (b 1928).

After 1911, George Lambeth does not appear again until 1932, when he is listed as staying with his parents in Draycott Avenue.

After Robert (d 1934) and Mary Ann Sherwin (d 1933) and William Inns (d 1967) passed away everyone else seems to end up in Australia.