After building the first London estates in a relatively short timeframe, the period between and after the two world wars saw a more intermittent pattern of building and regeneration for Guinness.

The 1920s saw a housing boom in England; with a rise in home ownership, while a number of new Housing Acts during the 1920s and 1930s saw improvements in conditions, including slum clearance and a clampdown on overcrowding.

World War Two brought bomb damage to the city and in its wake, a population boom and a raft of new policies on town planning, population dispersal and housing provision. The housing industry itself was changing, as councils became a major provider of rented housing and the government implemented a house-building programme to provide decent homes post-war. (Malpass, 1998)

Post-war council housing was heavily influenced by Raymond Unwin, the architect of the garden city movement. It moved away from the tenement-style housing of Guinness and the other established charitable providers, to a new kind of estate, made of terraced or semi-detached houses with more green space.

In 1913 the architect Charles Joseph’s scheme was approved at Kennington Park Road in Lambeth, London. However strike action in the building industry delayed the construction and then war came.

After the war, building work finally began in 1921, and Kennington Park Road was Guinness’s first development built with the support of government funding. The original plans proposed the usual pre-war architecture for 160 tenements, but new public demand for self-contained, cottage-style housing and separate bathrooms prompted a change in design.

The architect modernised his plans, adding separate bathrooms and reducing the height to four storeys. This meant that whilst earlier estates had been built for between £79 and £169 per tenement, Kennington Park Road cost £807 per unit (without the cost of the land). The rents were higher because of this, but this was the first rise in Guinness rent for 30 years. (Malpass, 1998)

During the first half of the 20th century, Guinness started a programme to modernise the older London estates. They added electricity, more space and separate bathrooms.

In 1925 electricity was introduced on the stairs and in the grounds at Brandon Street, Columbia Road and Lever Street. Bethnal Green Borough Council wired Columbia Road fully in 1930 and supplied electricity to tenants’ rooms via meters.

The next two estates took a slight step backwards, as although they featured self contained flats, tenants had to share bathrooms and sculleries. The Kings Road estate was built in 1929, on land given to Guinness on a 999-year lease. The estate gave preference to people living or working in Chelsea.

The Stamford Hill estate was built further out of the city centre than those before it, in Hackney. It was completed in 1932, and provided 400 units, which made it a very large development at the time.

In 1938 Loughborough Park in Brixton was the final development to open before World War Two. Designed by a new architect – Mr E Armstrong – for the first time in 30 years, this estate had bigger flats, more natural lighting and private bathrooms and kitchens. There were 1040 applications, plus 216 transfer applications for the 390 flats by December 1937.

The most extensive work programme took place between 1951 and 1959, where improvements were made to all of the estates except Draycott Avenue in Chelsea. The Trustees appointed the firm Gill and Bemister to carry out routine maintenance work on an annual contract after World War Two. (Malpass, 1998)

Between June 1952 and January 1960, at a cost of £250,000, improvements were made to 2,268 tenements.

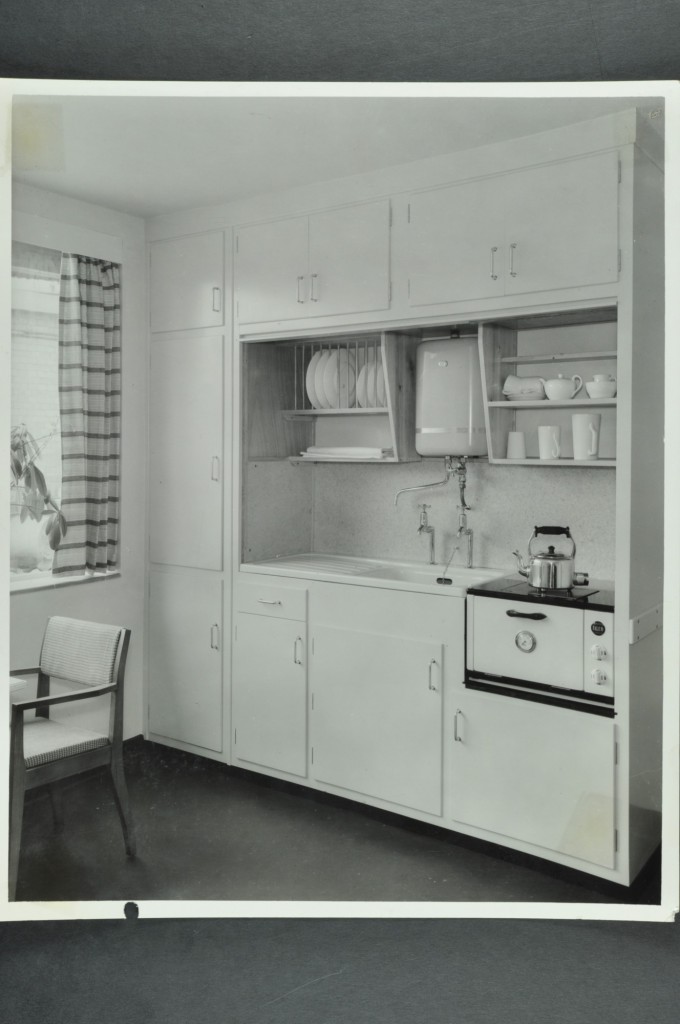

“The improvements carried out consist of bringing the water supply to each dwelling; fitting a sink in each living room, and hot water from a [gas-fired] Acot heater; putting a modern type of gas copper in place of the old and worn out solid fuel coppers in the small laundries on each landing; replacing cracked and discoloured glass in the landing and laundry windows; in order to let more light into the areas, stairs and passages, modern drying lines in the small laundries and putting 2 cwt, coal bunkers in the space released by the removal of the landing sinks.”

Paper for the Trustees, 1953

During the 1960s, Guinness started to sell some of the older London properties (including Brandon Street and Vauxhall Walk). New homes were developed, including Guinness Court, built in 1949; Iveagh House in Brixton, built in 1953, and John Street, Newham, built in 1955. No new land was bought for twenty years after the John Street plot in 1951, as the Trustees focused on investing in the modernisation of the properties it already managed.

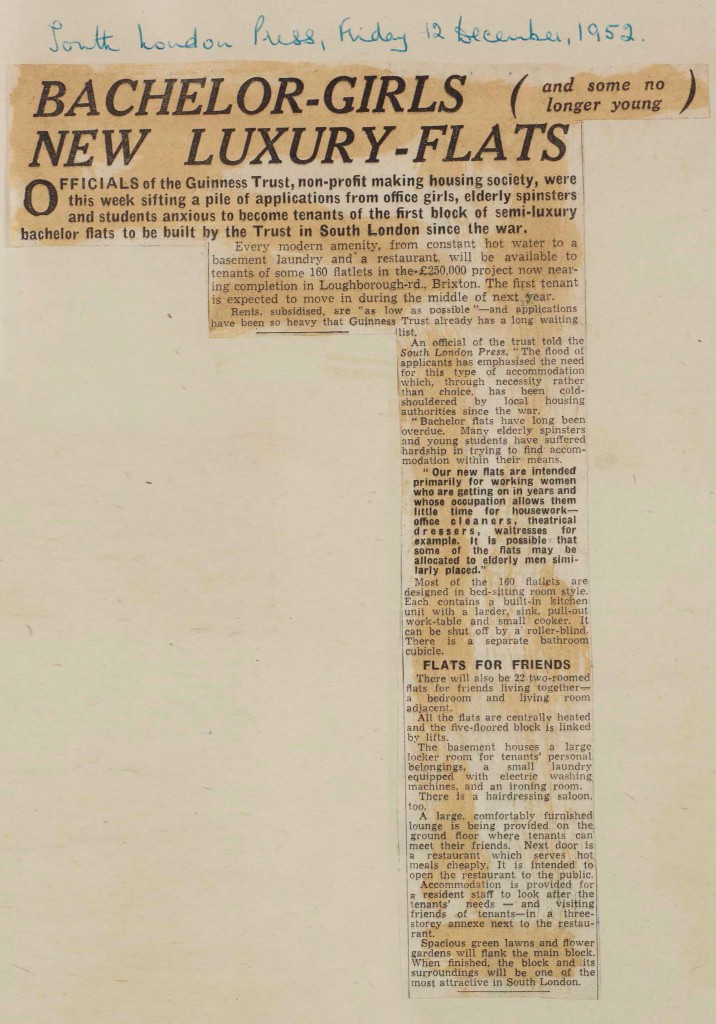

These new estates offered a new form of housing for single-person occupation and often for older people. Guinness Court was opened for “poor ladies from, say, 45 years of age and not for aged women” (Minutes of 17 June 1947) and was run in partnership with the Women’s Voluntary Service. Iveagh House, Brixton was marketed as secure and comfortable flats for single ladies, with separate accommodation for any overnight guests!

These developments marked a shift in the tenants that Guinness was providing homes for – as the population was changing, they weren’t just for working class families, but for anyone in need of good housing.

A newspaper article describing the new flats at Iveagh House

Some of the estates included hostels for homeless people and programmes to help with drug and alcohol problems. This work has continued with projects like Lorne House, Hackney, a centre for people recovering from alcohol and drug abuse run in partnership with Turning Point in the 1980s.

You can read about some of the forms of support we offer to customers – from financial advice to sheltered accommodation – in chapter 3.

As Guinness reached its 80th birthday in 1970, the Trustees knew that they needed to provide housing further afield for people as they moved away from the capital.

In 1972 Noel Barwick was hired as Director, bringing in a new strategy, including further modernisation and a plan to build outside London. By 1973, 16 dwellings had been built at Gosport, Hampshire – our first property outside London (excluding the Newhaven holiday home) – closely followed by new developments in Sudbury, Stevenage and Bracknell. (Malpass, 1998)

We began to work with other associations, forming partnerships and taking over the management of properties across the country.

Guinness’s purpose to provide decent homes for people who required them had begun to spread across the country, and would later be strengthened with the addition of many homes from other housing associations in the coming years.