Like many people in Britain, The Guinness Trust communities were greatly affected by the world wars of the past century. Buildings were damaged and staff and tenants left their homes to join the fighting.

In 1914 The Guinness Trust had 2,565 tenements across 8 estates in London; with Trustee Lord Rowton estimating that we were housing 7,327 tenants. (Malpass, 1998)

Unlike World War Two – when heavy bombing affected many of our estates – the original buildings went undamaged. But with materials and funding scarce, no new building work was started until Kennington Park Road in 1921. The land for this estate had already been purchased by 1913, so it was used instead as allotments to help with food shortages.

Many of the men who lived and worked at Guinness joined the armed forces and the Trust tried to help as it could, freezing rents at 1914 prices and continuing to pay half wages to those staff who had joined up to the army. (Malpass, 1998)

At Draycott Avenue, a memorial can still be seen to the residents who fought during World War One.

As soldiers returned from war, the government was keen to provide them with suitable homes, and a substantial phase of house building began under the ‘Homes Fit for Heroes’ campaign. Under the resulting Housing Act in 1919, councils were required to provide housing through subsidies for the first time. The Kennington Park Road estate was the first Guinness Trust property to be built with these subsidies.

At the outbreak of World War Two, The Guinness Trust had 3,682 tenements on 12 London estates. There were 42 major air raid incidents on Guinness properties, mostly during the 1940 Blitz, which saw five estates hit. By 1941, the Trust had spent £40,000 repairing war damage. (Malpass, 1998)

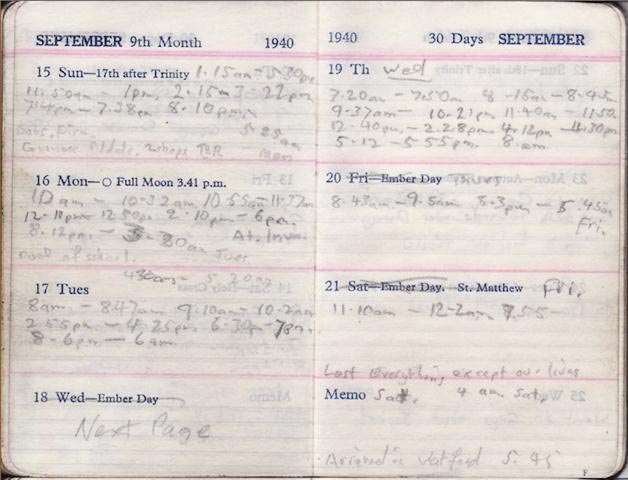

This diary entry from James I Mason, a fire watcher on Worthing Buildings in Bermondsey in 1940, records a bomb at Page’s Walk. The time relates to when he spotted bombs landing and 21 September is particularly poignant, reading:

“Lost everything except our lives.”

Diary reproduced with thanks to Jill Floyd.

Many of the estates offered additional shelter to its tenants. The ground floor of Lever Street was rebuilt as an air raid shelter and the trenches at the Kings Road estate are described by James Wheal, in his memoir:

“…a massive machine was digging a long deep trench in the yard outside our block at Guinness Trust. It zigzagged round towards the second block and had one main entrance and three or four emergency exits…. Kit [his brother] was worried about where he’d play football at first, but when the diggers had gone the trench was roofed and concreted, and apart from the entrance you wouldn’t have known it was there. What you couldn’t miss, however, was the fact that the railings that surrounded Guinness (before the war, one of the rules was that the main gates to the Building were locked at midnight) were torn out for melting down for the war effort. … At night in the Guinness yard all the outside gas lamps had been turned off and people picked their way across to their blocks with the aid of a small hand torch covered with red or blue paper to dim the beam.”

Donald James Wheal, World’s End, 2005

Other defences were less sturdy:

“From the first week [of the war] it became clear that London by night was the main Luftwaffe target… My father, as ever, began planning for the worst. The shelter in the yard outside our house had become a grim, damp concrete tunnel lit by low blue lights and lined by narrow wooden three-tiered bunks… Ever resourceful, my father converted the bedroom of number 3 into our own shelter. The bed had a substantial frame and barred-steel support for the mattress. By inverting it, he created a shelter about two feet high. Then using thick planks nailed and bound to the top of the bed, and as additional mattress from the Put-U-Up next door, he strengthened the shelter ‘roof’. My mother cut thick hessian and stuck it with carpenter’s glue to the bedroom window panes. With the black-out curtain pulled to we were safe inside. We hoped.”

Donald James Wheal, World’s End, 2005

2,287 Guinness residents were evacuated in September 1939, with all but 297 returning to London by December that same year. In 1940, more than 2,000 people were evacuated to the countryside again.

Donald James Wheal was one of those who returned in December. He describes the adventure that he and his friends found in this new London on their return:

“The 1940–1 blitz on London and the far less frequent air attacks that continued into 1942 destroyed over a million houses and damaged, in some degree, hundreds of thousands of others. It was normal in London to see streets of abandoned houses or gaps in terraces where two or three homes had been demolished by a smaller bomb…To boys of my age the bombing had opened up a vast and varied new playground. Within a few hundred yards of Guinness Trust there were literally hundreds of abandoned houses.”

Donald James Wheal, World’s End, 2005

Most of the estate staff were over 40, so they weren’t called up for active duty. However, 38 out of 43 men employed on the estates were fully qualified ARP (air raid precautions) wardens. 11 men were on active service by the end of 1941, including Mr Chappell, the Head Office accounts clerk, who stayed at the Trust until he retired in 1972. Three trustees also fought, including Lord Moyne and Viscount Elveden who were both killed during the conflict.

The Secretary’s report of 1940 describes the effect of the war on staffing at this time:

The war also saw Guinness’s first female superintendents. When their husbands passed away, the wives of the superintendents of Page’s Walk and Lever Street were employed in a job share to manage the Brandon Street estate.

The biggest single loss of life at The Guinness Trust estates occurred in one night and at one estate – the 23 February 1944 at the Kings Road tenements. Bombers – likely heading to destroy the power station at nearby Lot’s Road – found the Guinness Trust Building as their target instead. Half of the 160 tenements were destroyed with the rest damaged. 59 people lost their lives that night, including Superintendent Caple and his wife.

Donald James Wheal was on the estate with his family at the time of the bombing. He describes the night as such:

“Everybody in the flat, and I’m sure the occupants of every other flat in Guinness Trust, was listening to the uneven rasp of bomber engines in the brief gaps between exploding AA shells. As we remembered it afterwards, we all knew that these particular bombers were for us… All over Guinness Trust Buildings… people stiffened as the first 2,000lb high-explosive bomb screamed down and exploded in Upcerne Road, between us and Lot’s Road power station. Seven of my mother’s girlhood neighbours were killed outright…”

“…At the corner of the block we all stopped, staring aghast. Smoke and dust whirled around our heads. Orange light from the gas main gilded the roof of what felt like a huge sparkling cave in the dust-laden air. Within the ‘cave’ the corner of Block 3, twenty or thirty flats, including Auntie May’s number 84, was one enormous pile of rubble, concrete, sections of brick wall, doors, sinks, beds, flapping bits of clothing…. Behind it, the sixty-foot front wall of Block 4 had been ripped off. In the light from the gas main we stared at exposed rooms that were like an open-fronted doll’s house. Except there were still people moving inside it.”

Donald James Wheal, World’s End, 2005

My mum was actually in the block when it was bombed and a lot of people were killed in that Blitz. I think the pilot was just discharging his load, trying to hit the power station which is over the back from the estate. My mum never really talked a lot about it, but she said that her friend was killed. She was actually evacuated, but she’d come home that weekend, so it was just the luck of the draw.

My grandad was in, like, the land army looking after the area. After the bombing, my nan used to tell me that they went down to the station and he was sitting having a cup of tea, whilst this was going on, because it was a very quick hit.

A lot of people then were moved into temporary accommodation until they were moved back in for rebuilding.

“Jo Oakham, a Chelsea Civil Defence worker, kept a diary throughout the war and a record of the bombs that fell on Chelsea on February 23 1944. She was sent to Guinness Trust in the immediate aftermath of the raid [extract from her diary] ‘22.07 Sirens. Most awful barrage and a spectacular sight of flares and gun flashes. 22.34 Four bombs fell all together on the World’s End. 23.12 All Clear. Got sent to Guinness Trust which had a heavy bomb on the third wing (block) … and gas main in Kings Road was alight in crater full of water. The two other bombs were Upcerne Road and Lamont Road. It was a truly awful night, The Guinness was one awful heap of rubble and the other blocks were terribly blasted. It was reckoned 200 people were underneath, trapped, and to crown it the heap was smouldering all night. The gas main was late got out. Work proceeded on Guinness all night (and all day and all the next night). There were queues at the First Aid posts of injured – Rest Centres were full of homeless. We were all up all night doing whatever came along – at any time.'”

“Most people were killed in the upper floors of E entrance Guinness Trust… My cousin Margaret’s extra VAD watch had meant that Kit and I weren’t sleeping in number 84 that night. The flat was empty and under countless tons of brick and concrete by the morning. At number 81, Samuel Robert Caple, in his orange tweed trousers and waistcoat, and wearing a body-belt no doubt holding scrupulously accounted for Guinness Trust rents, was crushed and burned to death, as was his wife, Mrs Mabel Anne Caple.”

“Round the Hundreds [another block] was the saddest sight. You can look at pictures of destruction and be shocked. It’s quite different to look at the destruction of buildings you have known every single day of your life. Different to understand that the men moving over the huge mound of rubble were searching for people you knew, with names you can name.”

Donald James Wheal, World’s End, 2005

A memorial stone at Caple House (rebuilt and named after the superintendent who died there) acts as a tribute to the 59 victims of the Kings Road estate attack.

The North East Surrey Crematorium at Morden in Surrey is also home to a memorial for victims of the attack buried there.

Chimney sweep, Anthony Smith, fought during World War One, seeing action in France until an injury forced him home in 1917. During World War Two he joined the Chelsea Division of the Civil Defence Rescue Service and witnessed the devastation wreaked by German bombs at Kings Road on the night of 23 February 1944. He set about rescuing people trapped in the rubble of the Guinness estate, working all night to free victims and recover bodies. In 1944 he was awarded the George Cross – the highest award for civilian gallantry

– for “outstanding gallantry and devotion to duty in conditions of the utmost danger and difficulty.”

After the war he returned to his life as a chimney sweep and died in 1964. (Steve Hunnisett and Wikipedia)

This bulletin lists the damage done to the London estates during air raids and the lives lost during World War Two.

At the end of the war, parties were held in the estates with celebrations and street festivals to celebrate Britain’s victory.

The war brought bomb damage to much of London, as well as new policies on town planning, population dispersal and housing provision. By 1945 479 dwellings were rendered uninhabitable on 6 estates – 13% of our stock at the start of the war. However devastating the effects of the war, the damage it caused gave the Trustees an opportunity to modernise the old estates more quickly. For the next few years, Guinness concentrated on rebuilding and improving the tenements for the generations to come.